This week, our assistant director (and resident Trayn’d Bandes gardener) Chris Budnick puts his vast knowledge of gardening to use, as he discusses the line between farming and gardening, the agricultural revolution and how over time, these things shaped the world of European culture.

To talk about the history of gardening, one must first consider the history of agriculture as a whole. The agricultural revolution took the natural availability of plants and put it into the hands of man. Since then, our entire civilization has been built on this ability to use dedicated land for food (and other useful plants) production.

But where is the dividing line between farming and gardening? Some argue that a farm has a large area covering many acres. Tell that to the many vertical farms springing up urban environments that have the “footprint” of only a single building. Some argue that farms have a mix of both plants and animals. However, many farms produce a single crop, while urban and suburban homes have goats and chickens on their property. Some argue that a farm feeds many, while a garden feeds a single family. But what of the many community gardens that spring up, supplementing the meals of many families? Perhaps you argue that a garden can be tended by a single family, but a farm takes many to manage. Yet, mechanization and automation of farming equipment allows for single families to tend many fields at once. Or is it possible that farms are for essentials (food and medicine) where a garden is only for pleasure? One can assume that the tulip farmers of Holland, a major international industry, would strongly disagree.

As one can see, the line between modern gardening and farming is becoming increasingly blurry. For the sake of this article, we are going to focus on gardening and agriculture in the renaissance. That is to say, before the advent of the industrial revolution. Further, this allows us to define a garden as such: A smaller area of land, personally owned, that can be maintained by a single family or small group of people, and can be either for practical purpose, pleasure, or both. This article also plans on addressing garden design primarily of European culture, as opposed to the rest of the world within the same scope of time.

However, the roots of gardening, if the pun can be excused, go much further back than the renaissance. Renaissance translates to rebirth and the design of gardens is no exception. Many renaissance garden designs originate with the gardens of the Roman Empire. These in turn, have their origins in the Persian Empire, which spread its influence to the Mediterranean region.

The idea of man creating an earthly paradise is an old one. In fact, the English word paradise comes from the

The Persian Garden, a world heritage site, is actually a collection of nine gardens spread over nine provinces in present day Iran. (UNESCO)

Latin paradīsus, and the Greek parádeisos. Both of these can trace their origin back to the Old Persian paridaida, literally “walled around” or “enclosed space”. Thus, the earliest gardens were walled gardens.

Of the styles derived from this concept, Charbagh is perhaps the easiest to visualize. Bagh is the Persian word for garden and Charbagh (Four Gardens) features an enclosed space of right angles, dividing the grounds into 4 sections. These are often divided by streams or tiles designed to imitate water. Here the garden represents Eden as a whole, and the four Zoroastrian elements of earth, air, water, and plants.

Other cultures of the time, such as the Minoan or the various Egyptian dynasties also began developing gardens for various purposes. These regions focused more on creating paths through naturally beautiful areas of untamed nature. However, over time even these would eventually shift towards a more purposefully designed approach.

Ancient Greek culture is unique in that it did not favor stylized gardens. Certainly personal space and gardens were both known concepts, but the two were not combined into anything resembling the Persian walled gardens. This much is made clear in their writings about other societies, which handles the topic of gardens with some

Right: An aerial view of the gardens of the Taj Mahal in Agra, India. While built nearly 2,000 years after the first Persian Empire, it clearly shows the strong influence of Charbagh style gardening on surrounding cultures. (Alias)

uncertainty. For all their philosophy and study of the natural world, the Greeks are also incredibly remiss in their description of flowers and other plants that might be kept for pleasure. The most common mention of flowers in classical Greek literature mentions their use in garlands (roses and violets being favored).

The Roman Empire, which liberally borrowed and modified ideas from other cultures, would have started adopting these gardening practices around 60b.c.e. Prior to this, gardens were common, but they were small and utilitarian. They would likely be situated close to the home and would supplement what was grown in the fields. Gardens would often include plants with pleasant smells, or those plants that required a greater level of care and attention from their growers, than what they would get from the farm field.

As the influence of surrounding cultures seeped in, Roman gardens became less utilitarian and more splendid. They became walled like the gardens of Persia. They were filled with religious meaning and iconography, like the gardens of Egypt. They provided peace and refuge from an urban lifestyle, while simultaneously reminding the plebes that the aristocracy, which built such wonders, held the power and the purse strings. Gardens were elaborately designed with shaped paths, raised beds, and elaborate irrigation systems. Depending on the available space they could be raised in terraces or lined with rows of trees, which was quite popular.

Eventually, these gardens would become more and more private, reserved only for the wealthy and their associates. However, owning a garden also became a symbol of status. The middle classes of Rome started to build gardens in reflection of their betters, though much scaled down in size. While limited in variation compared to modern gardens, Roman horticulture favored a wide range of flowering plants, including roses, violets, poppy, and the gladiola (often called the sword lily as gladiolus translates as little sword).

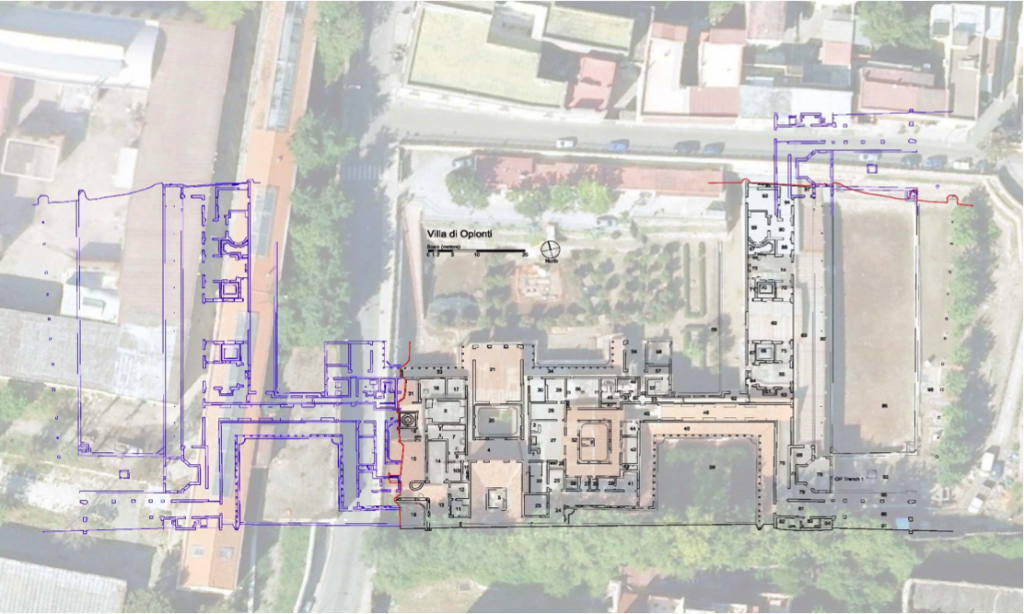

Above: Villa A at Oplontis, Torre Annunziata, Italy, an excavated roman villa at Pompeii. Buried in the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, and currently being recovered. The image shows the large villa garden, surrounded by recovered and (superimposed) hypothetical remains. (Clarke)

A view from the garden facing towards Villa A at Oplontis. Paths, and gardens plants can be seen in a state of semi-reconstruction. (Clarke(

Roman gardens of size contained many elements. Waters features were very common, fed by the house cisterns. Oftentimes a patio was build looking out over a lower garden, and served as a point of departure to wander the grounds. Paths would wander throughout, designed to showcase and highlight specific parts, and shrines would be enfolded into the vegetation. Mosaic tiles were also extensively used to highlight certain areas of ornamentation. Gardening had reached the level of personal artistic expression, and while access to the space was shared, evidence from the writings of Pliny the Elder clearly mark the domain of the garden as that of the matrona, the wifre of woman of the house. (Stackelberg)

Unique to roman forms of gardening was the emphasis placed on ars topiaria, the art of cutting, bending, and twisting of shrubs into fantastic shapes. It was common to see bushes made to resemble animals, ships, and symbols. So important was this aspect of gardening that the title of topiarius is the name given to the best ornamental gardeners. Cicero cites the development of ars topiaria to Gaius Matius around the end of the 1st century b.c.e. and names the topiarius as among the higher class of slaves. (Stackelberg)

Of course, much of this was lost when the Roman Empire fell. Ruins still exist where we can see the infrastructure that existed to support these gardens, but any functioning gardens are merely the copies made by much later generations. So it was that in the medieval period, the garden fall back into a much more practical role. Personal homes might have one for food supplementation, or to try and cultivate basic medicinal plants, but the real champions of the garden were the monasteries.

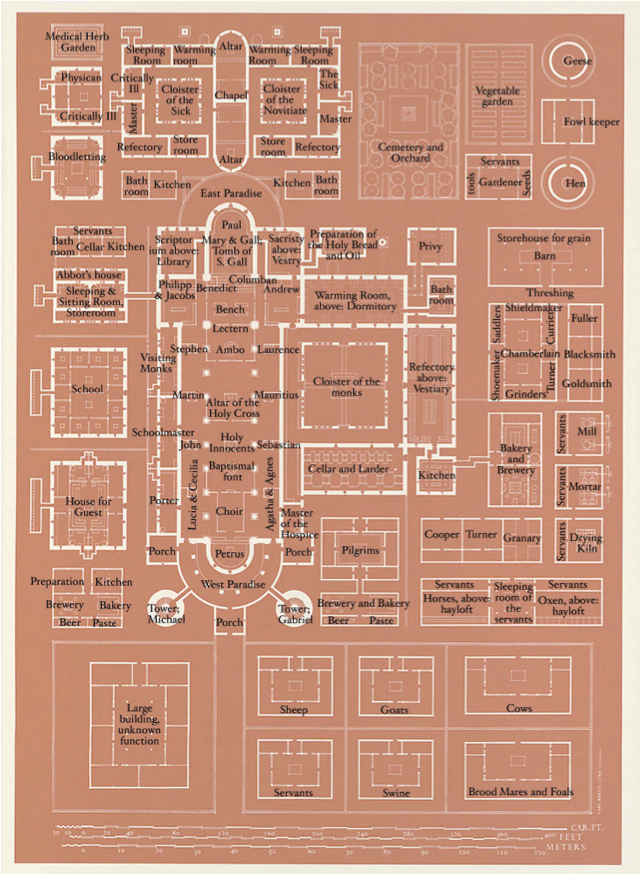

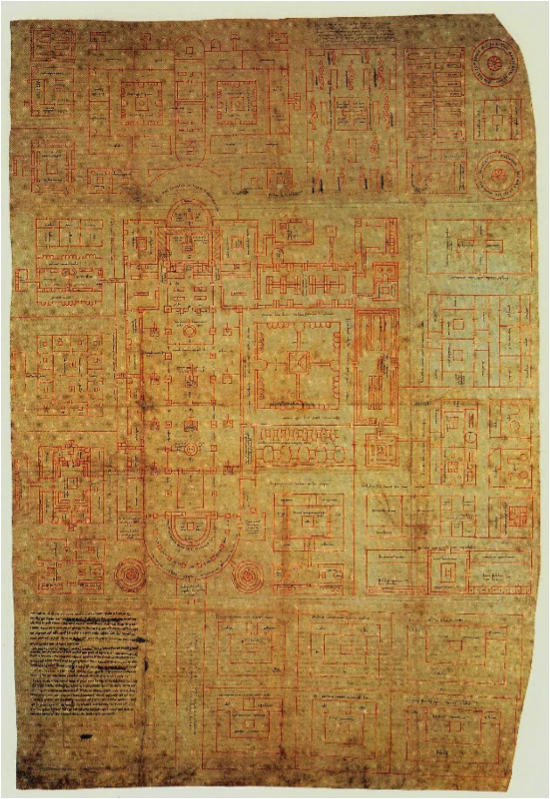

The original Plans of St. Gall, made of 5 sheets of parchment, sewn together, and labeled in Latin. (The Plan of Saint Gall)

Monasteries were cultural touchstones for European society, but they were economic ones as well. Monasteries were places of relative stability in the world, and their gardens reflected this. While they may have relied more on natural availability than their roman predecessors, they took advantage of many of the techniques of roman gardeners as well. Monastic gardens benefitted from enclosed spaces, where plants could grow in shelter. Raised beds helped with drainage, and tiled ditches were used to carry water and aide with irrigation, often flowing from or feeding into strategically placed cisterns. Here, gravity provided the primary power source and often gardens were grown on a terraced incline to take advantage of this. And while the monks may not have understood the chemistry of it, it was quite common for manure to be dissolved into these cisterns to promote fertilization.

As monasteries grew, the gardens often spilled out from the enclosed areas to encompass the surrounding land. Orchards could provide food as well as medicinal crops. Furthermore, an established orchard would produce fruit and nuts for years, while needing far less daily care than a farm field.

Monks also were great lovers of flowers, and spaces for them were often specifically set aside when designing monastery grounds. A unique example is the blueprint for the Plan of St. Gall (c. 820). Though never actually built, it remains as the only surviving architectural planning document of a large scale structure from the medieval period. It was designed as an “ideal” monastery, and is thus an excellent insight into what structures were given greater or lesser importance. In the center is a cloister square that allows for walks through beds of flowers. The chief physician’s house is bordered by an orderly garden of medicinal plants. Many other buildings on the featured peristyles (columned areas with winding paths and gardens) such as schools and guest houses, a design taken from ancient Rome.

It is perhaps ironic that the monks of the time had such a love of flowers. The early Catholic church had first labeled this as a pagan tradition, but quickly saw that it was an untenable position. So the church did what the Roman Empire had done before, it absorbed these pagan cultures into itself and relabeled them as purely Christian. Roses and lilies, popular to roman gardens, became symbols of purity and the martyrdom of the Virgin Mary, respectively. This was perhaps most clear in the cemetery gardens, common to monasteries of the period. These offered a location of peace and tranquility, amid myriad symbols for Christian contemplation. (Gothein)

However, the ultimate purpose was to feed the monastery itself, which needed to be self-sufficient enough to support its local community. The diet of monks would have been largely vegetarian, favoring plants from the onion family (onions, garlic, leeks, & shallots), the mustard family (mustard, broccoli, kale, cabbages, & turnips), the parsnip family (parsnips, carrots, celery, & parsley), and the legume family (beans & peas). Certainly there are more than can be named here, and each monastery can be expected to favor those plants which were naturally available in the local ecology.

Alongside vegetables, herbs were also grown. However, the term can be misleading to the modern gardener, as herbs in the medieval period were used for more than just the flavoring of food. As said earlier, monastic gardens often grew plants for medicinal purposes and many herbs fell into this category. Especially favored by the monks were those plants which had multiple edible parts or purposes. The following list (McGann) is a sample of some of the plants that would be common in a medieval garden.

- Angelica (Angelica archangelica): Common to northern Europe, Angelica was considered a remedy for most poisons and a ward against infectious diseases. Hospitals might have is planted around the building to prevent the spread of disease.

- Betony (Stachys officinalis): Considered a cure-all for many ailments. If a medicinal garden had a single plant, it was likely this.

- Black mustard (Brassica nigra): Almost every part of the plant in the mustard family is edible. Seeds can be used in pickling and to make mustard. Leaves are edible in salads.

- Cabbage (Brassica oleracea): This is a diverse family. Different cultivars have been bred, focusing on enlarging different parts of the plant. Members include broccoli, Brussel sprouts, cabbages, cauliflower, kale, kohlrabi, & savoy.

- Camomile (Chamaemelum nobile):

- Chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium): A relative of parsley used primarily in mild food dishes. Considered a staple herb of French cuisine.

- Clary (Salvia sclarea): A type of sage. Its seeds possess a stick coat, and were often placed under the eyelid of someone with “something in their eye”. The seeds would stick to the irritant, and could be easily removed.

- Comfrey/Knitbone (Symphytum officinale): A Balkan native, grown for medicinal purposes. It was known to help heal injuries, reduce inflammation, and (as its name might suggest) help to set broken bones. It is not recommended for internal consumption due to toxicity levels.

- Coriander (Coriandrum sativum): This Mediterranean and Asian native is also known as cilantro. It was prized for three parts: the spice its seeds offered, the flavor of its greens, and the fragrant oils that could be extracted from its flowers.

- Cumin (Cuminum cyminum): Medicinally, cumin was used to calm digestion. It has an earthy flavor and was often powdered and used as a soup/stew additive.

- Dill (Anethum graveolens): Dill has diverse uses from the familiar pickling to the flavoring of soups, fish, and sauces. It was used medicinally to aid the stomach, liver, headaches, and boils. Easy cultivation and preparation made it very popular.

- Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare): A relative of carrot, celery, and dill. Fennel has an anise-type flavor and was cultivated for use of seeds, greens, and edible bulb.

- Fragrant tansy/tansy balm/Costmary (Tanacetum balsamita): A fragrant flowering herb, with a wide range of medicinal uses (though the specifics vary wildly).

- Hyssop (Hysoppus officinalis):

- Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia): Grown in both medicinal gardens and home gardens, this plant is highly aromatic and was held to have multiple remedy uses. Tolerant of a wide range of growing conditions, this Mediterranean native made its way throughout much of Europe.

- Parsley (Petroselium crispum): A popular herb for seasoning. As a relative of carrots and celery, its root was also edible. Oil pressed from parsley was used as a diuretic.

- Pennyroyal (Mentha pulogium): A member of the mint family, it was a popular culinary additive in the medieval period. Sometimes used as an abortifacient, its toxicity has gradually led to its disuse.

- Pot Marjoram/ Oregano (Origanum vulgare): Another member of the mint family native to the Mediterranean basin. Extremely flavorful and an attractor of pollinators. Its medicinal use varies with time periods and cultures, covering a wide range of purposes.

- Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis): A perennial, woody herb that had spread throughout Europe by the 1400s. Drought tolerant and easily grown, it has symbolic connection to the Virgin Mary.

- Rue (Ruta graveolens): Brushes of rue were used by the Catholic church to sprinkle holy water, earning it the nickname herb-of-grace. In foods it adds a sharp bitter flavor. It was used as a purgative (to induce vomiting) due to its high toxicity, but its high toxicity and tendency to cause liver damage have led to its disuse.

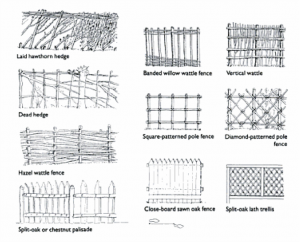

Several wattle fence designs, showing the diversity of the material and the possible patterns. (Landsberg)

Yet, the monasteries did not have a monopoly on gardening. Personal home would have a garden for much the same purposes, though obviously on a much smaller scale. Gardens represented a source of additional food, medicine, and sometimes income, and as such they needed protection. Gardens were often surrounded by thorns, ditches, earthen banks, or the ubiquitous wattle. And while brick and stone might be the hallmarks of a wealthier class, wattle fencing is by far the more widespread choice. It was so common that religious imagery of the time depicts the Garden of Eden walled by wattle fencing. Hortus conclusus, a Latin term for enclosed garden, became both a symbolic title and art depiction form for the Virgin Mary. (McAvoy)

Wattle fencing is so ubiquitous as to defy a search for its origin. It is made of woven saplings in a variety of forms, to suit a variety of functions. This material is durable, flexible, and can be readily gathered from nature. Combined with the need to protect the garden from animals, thieves, or the competing local ecology, the wattle fencing has been possibly the most widely used barrier constructed by humans throughout history. Further, wattle framework is easily combined with daub (mud, wet sand, dung, and/or clay) to create sturdier and more resistant walls.

With the opening of the New World to Europe, one would assume that many things about the European diet would change as markets were flooded with new produce. However, the opposite proves to be true. Exotic plants were transported from the Americas, but doing so was difficult, and not all plants travel equally well. Some plants had obvious crop value, such as maize. Others like amaranth were familiar enough to their European varieties, that they could be recognized and cultivated. However, many plants were simply so unknown that were avoided by Europeans.

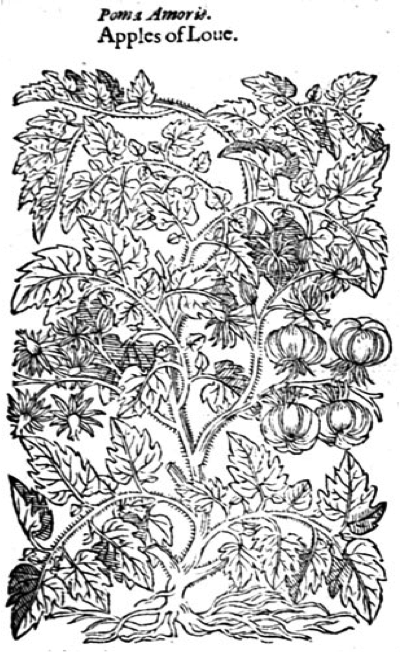

A woodcut drawing from John Gerarde’s The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes. The tomato, or love apple as it was called at the time, is grouped quite correctly with several other members of the nightshade family. (Gerard)

One ironic example of this is the tomato. The tomato is a member of the nightshade family, along with potatoes, eggplant, chili peppers, and bell peppers. And while many of these would have been unfamiliar to Europeans, nightshade is not. Nightshade is very toxic, owing to the alkaloid compounds found in all of its parts. Its scientific name is Atropa belladonna, coming from two sources: Atropos, the Greek Fate who cut the thread of life, and belladonna from the Italian for “beautiful woman”. In dilute form, the toxins can be dropped in the eyes, causing dilation of the pupil, which was a mark of beauty at the time. Aside from this cosmetic use, it was also used by the romans as an anesthetic during surgery, and as an outright poison. Well familiar with the appearance and effects of the nightshade family, the tomato and many of its kin were avoided in Europe for many years before being proven safe to eat.

As gardens have changed over the years, it is perhaps counterintuitive to think that the tools for maintaining them should not. Trowels, rakes, hoes, and shears are all examples of garden tools that have shown little variance over time. The wheelbarrow was developed around the 2nd century b.c. in China and would be recognizable to the modern farmer. So even with the import of rare and unknown species, local gardens were slow to change. Certainly, large scale agriculture has been overhauled by the industrial revolution, but the hand tools of the garden have benefitted primarily from improvements to the materials they are made of.

Looking back at the millennia that humans have engaged in horticulture, a pattern can be discerned. When civilization struggles and the average person grows food for their very subsistence, gardens tend towards the practical. They provide the medicine, vegetables, herbs, and fruits that are meant to supplement the cereal grains that come from the farm fields. However, in times of relative stability, gardens could become things of opulence. They provided retreats from the stresses of the world, and were a manifestation of wealth that others could see. As the renaissance bloomed, so did the ability to create a blooming paradise on earth, all within the walls of a garden.