It is widely known that Ireland was, at least nominally, under the control of England in the sixteenth century, and indeed for several centuries prior and for several centuries following. It is also generally understood that many Irish took issue with English control and resisted it. Beyond this, sixteenth-century Ireland typically remains hazy in the popular consciousness. For the English subjects of the sixteenth century, however, Ireland was a point of major concern. On the one hand, generations of English monarchs and nobles had tried unsuccessfully to make the “wild Irish” into upstanding English men and women, a problem made all the more pressing by heightened religious tensions following the Reformation. On the other, Ireland offered a fairly substantial market, both on the part of English colonists and the Irish themselves, to be served by ports like Bristol.

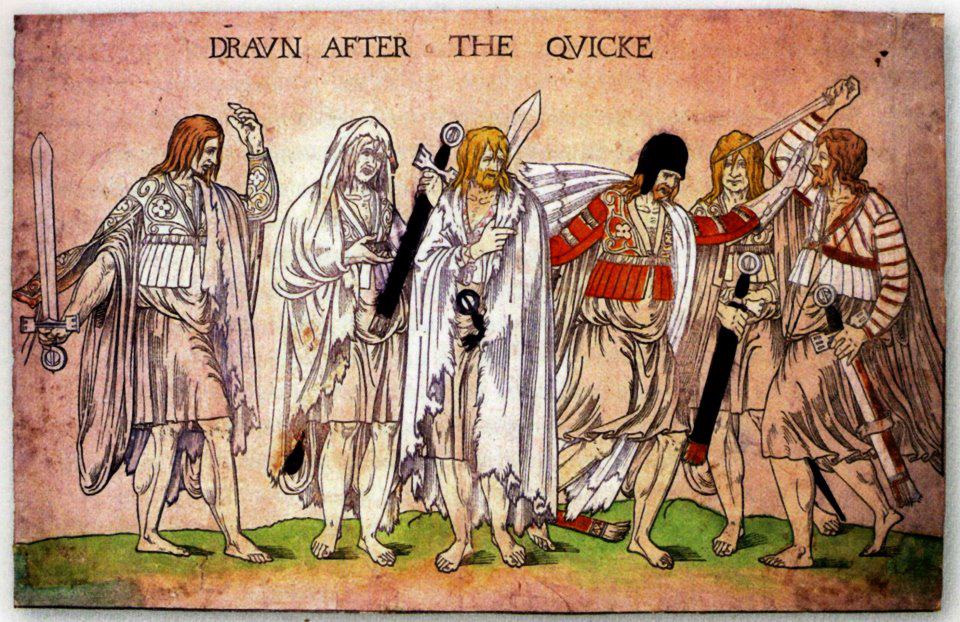

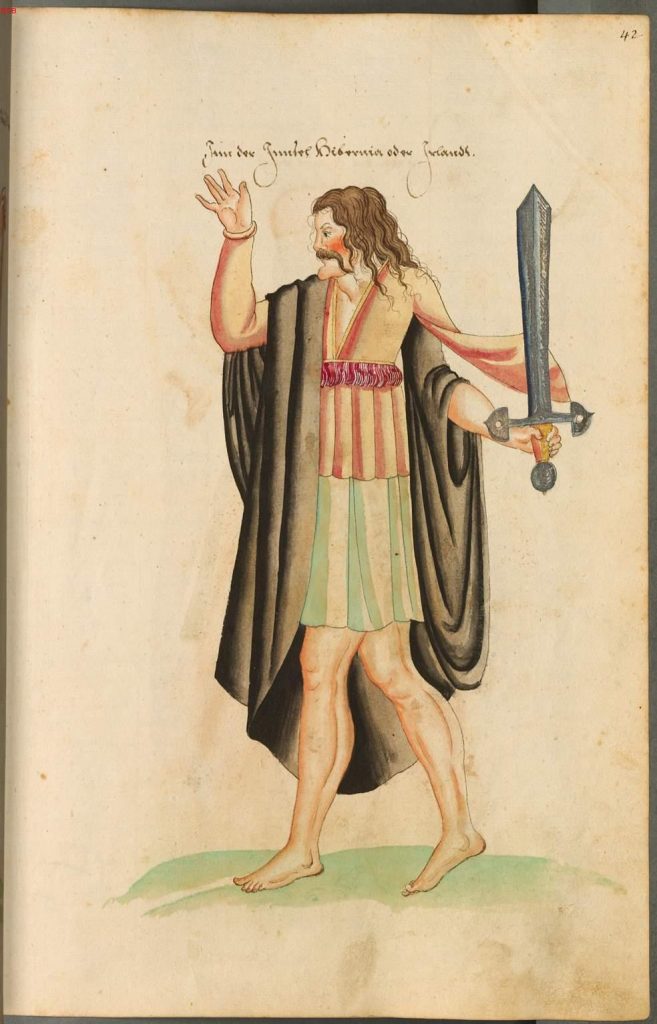

For common Irish people, clothing was fairly simple. Men wore wide-sleeved linen shirts, often dyed a yellow saffron color. To the horror of English commentators, common Irish women dressed much the same, wearing an ankle-length smock and little else. Those of higher status might wear overgarments similar to the kirtles and doublets worn by the English, but even these were adapted to accommodate the billowing sleaves of Irish clothing. Illustrations from the sixteenth century show Irishmen wearing their hair loose and long, but English observers from the period remarked on the ubiquity of the “glib” hairstyle, characterized by a short cut around much of the head save for long bangs. Irish women of the period were described as wearing their hair in long braids, or else up in a “great linen roll.”

The most iconic element of the Irish appearance, at least in the minds of English commentators, was the mantle, essentially a large woolen cloak that could be draped about one’s person. For common Irish people, such a garment was simple and practical, serving as protection from the elements and even makeshift shelter while traveling. That said, there are records of more ornate mantles being worn by higher status Irish people, featuring finer fabric and satin or even gold fringes. In a textbook example of moral panic, Edmund Spenser, an English poet and polemicist on the subject of Ireland, insisted that the ubiquity of mantles facilitate crime, promiscuity, and rebellion. While there were no doubt Irish fugitives who did use their mantles to avoid the authorities, the requests for mantles by English soldiers stationed in Ireland suggests that their popularity had more to do with their utility in a cold, wet environment than their value as a disguise.

In addition to their clothing and haircuts, the succession laws of the Irish were another point of concern for English observers. Perhaps most notable was the Irish succession practice of tanistry. Rather than authority passing from a chieftain to his eldest son (the system of primogeniture commonly practiced in England and much of Europe), rulership passed on to a designated successor, or tanist, who had the acclaim and general support of the leading subjects of the realm. This tanist was typically the next eldest or most prominent member of the chieftain’s family, often a brother or cousin. Upon the tanist’s accession to the chieftainship, he was brought to a designated hill where he placed his foot upon a ceremonial stone and swore his oath of office, followed by his newly elected tanist. English commentators were aghast at the apparent deprivation of the firstborn’s birthright, and Spenser speculated that this system of succession accounted for why the Irish would not acknowledge Elizabeth’s royal authority.

Within a chieftain’s domain, he had direct control of what was called the “loughty” or “mensal land.” Under him, the various court officials- his harper, his bard, his marshal, etc., all of whom came from specific families who each produced such officials- all had lands set aside for their own use and upkeep. A significant portion of the rest of a given chieftain’s domain was divided amongst the septs (roughly analogous to Scottish clans) who owed loyalty to him, each of which operated under the same tanistry system as their lord. Of the remaining land, that which was owned outright by any man was traditionally divided among his sons, rather than passing entirely or primarily to his eldest son, upon his death in a system called gavelkind succession. The rest was rented out on a yearly basis to tenant farmers. Just like in matters of political succession, English observers found Irish inheritance customs abhorrent, responsible simultaneously for the Irish becoming lazy and complacent but also barbaric and numerous enough to fight back against English encroachment.

And fight back they did. The bulk of Irish soldiers in the sixteenth century were kerns, deriving from the Irish word ceithern, meaning “troops” or “warband.” By and large, kerns went unarmored, although some were depicted with armor on their arms or described as carrying wooden shields. As for weapons, the kern traditionally entered battle with “darts” (small javelins) or a short bow and a sword or sgian (knife, in this case a rather long one). That said, kerns in English service around the middle of the century were outfitted with matchlock firearms, the knowledge of which they brought home with them after campaigning abroad.

Behind the mass of kerns in an Irish army were the gallowglasses, heavy infantry forming a sturdy rearguard. Rather than the single-handed swords or long knives of their kern fellows, gallowglasses typically carried long axes or two-handed swords. In a further contrast with kerns, gallowglasses wore armor, whether in the form of a long shirt of maille, a heavy padded coat, or some combination of the two, along with a steel helmet.

The Irish did field cavalry during the sixteenth century, but to a lesser extent than much of the rest of Europe. Riding without stirrups, Irish horsemen were unable to strike their enemies with the same force and follow-through of Continental knights. Irish horsemen were outfitted in maille shirts over padded coats, much like gallowglasses, and there is evidence to suggest that some Irish warriors filled both roles, fighting on foot or on horseback as needed. Based on their depiction in Image of Ireland, Irish cavalrymen carried spears to be thrust in a downward stabbing motion, rather than the couched lance of late medieval knight, along with a round shield and an arming sword.

Irish armies of the sixteenth century heralded their approach with bagpipes, rather than the trumpets favored by English and Continental armies. Upon engaging their foe, the attacking Irish force would raise a warcry, often in the form of heroic ancestor or paragon, although “ferragh” or “pharroh” were reported as universal favorites. Kerns then loosed their arrows and darts before falling on the enemy with sword and knife. Following along behind, gallowglasses would enter the fray, mopping up those enemies who withstood the shock of the first assault.

This is by no means a complete account of Irish culture in the long sixteenth century. There is much more that could be written about their customs, diet, economy, religion, or any number of topics. For the time being, however, we hope that this brief overview of the Irish civilians, political structures, inheritance laws, and warriors encountered by English subjects like those portrayed by GSM-Bristol has made your St. Patrick’s Day an enlightening one. Slán leat!

Author bio: Michael Lowry Lamble has earned an MA in Museology from the University of Washington and an MA in Medieval and Renaissance History from Loyola University Chicago. After playing some four hundred hours of Crusader Kings II, he was excited to read about tanistry and gavelkind succession in sixteenth-century primary sources for a change.