This week, our assistant director (and resident Trayn’d Bandes gardener) Chris Budnick puts his vast knowledge of gardening to use, as he discusses the evolution of gardening throughout Europe during the Renaissance.

As Europe entered the Renaissance and recovered from the Middle Ages, so too did the concept of gardening. Here again is seen the effect that general prosperity has on the use of gardens. The cultural rebirth of Europe, spreading outwards from Italy, was accompanied by an economic revival as well. Increased trade, communications, and ideas all came together to help nurture society as a whole, and provided a fertile bed for the gardening arts.

During the Renaissance, Europe looked backwards to the “golden age” of Ancient Rome and Greece. They copied art styles, architecture, and many other aspects of culture that had been lost during the centuries between. One should not then be surprised to find that the earliest gardens constructed for means other than subsistence were created where the Renaissance began, in Italy.

One of the earliest to write about what would become known as Renaissance gardens was Pietro de’ Crescenzi. He

The Villa Medici in Fiesole (north of Florence), created around 1455-1461 by Giovanni de’ Medici. (Gardens in Tuscany)

wrote a treatise called Opus Ruralium Commodium which outlined principles of a proper garden layout. He wrote about geometric proportion and the ornamentation of gardens with trees and shrubs trimmed into shapes designed to mimic roman architecture.

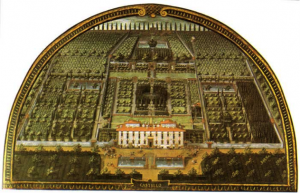

Following in the footsteps of their Roman forbearers these gardens were created for both pleasure and to display the power of the wealthy. Whether for public use or private, these gardens were a message to all that the wealthy had the power to create great works, while the poor did not. An excellent example of this is the Medici family, a ruling dynasty in Florence Italy that used the construction of gardens to advertise their wealth and add to their reputation.

A lunette (painting in a semicircular architectural space) of Villa Castello in Florence, Italy, by Giusto Utens (1598) (Gardens in Tuscany)

Donato Bramante, an Italian architect of the late 1400’s further wrote about proper garden styling. He was one of the first to focus on the perspective which a garden should be viewed from. In his opinion, the villa or household should be the midpoint, from which the view of a garden is seen. From there, a garden should expand symmetrically outwards. This idea would become one of the staple features of Renaissance garden design.

However, gardens also represented something more. They represented the idea that human beings could reshape nature to their will, more perfectly than their Creator had. They were symbols that mankind had the ability to reorder nature as they saw fit, denying the downtrodden position that civilization had been forced into for centuries. This is reflected in artwork of the period, showing that nature is not a perfect creation. Rather, it is the perfect inert material of creation, which mankind had the authority and duty to refine.

Renaissance Europe looked back to many sources for inspiration to recreate the classics of Rome and Greece. One such author they drew upon was Vitruvius, a roman artist and architect of the 1st century b.c.e.. Vitruvius held to three ideals, called the vitruvian virtues, when planning a building of any kind. He stated that all good constructs have the qualities of firmitas, utilitas, and venustas (solidity, usefulness, and beauty). The reader might recognize this name, whose ideas on proportion of parts to the whole inspired Leonardo Da Vinci’s drawing of the Vitruvian Man.

As the Renaissance spread outward from Italy, so too did the idea of the garden, though the migration of ideas was not always hand in hand with peaceful trade. Returning from was in the late 1400’s, King Charles VIII returned from war in Italy. He brought back with him ideas and people. As with many popular cultural movements, French renaissance gardens started with the upper class and moved downwards. Charles VIII had several gardens commissioned. Two monarchs later, Francis I was still building gardens. The Château de Blois featured gardens of flowers, fruit, and vegetables. It featured the very first orangerie (a building in which to winter potted fruit trees) in France, which survives to modern day.

The ideas of Italy continued to influence and refine the French gardens. These were designed with symmetrical paths, rows of trees and geometrical beds of plants. Pools of water were common and the use of statuary in gardens was exceedingly popular, although writers of the time warned against the use of ‘obscene’ statuary. Once again drawing upon the inspiration of classical authors, gardens were placed below the place of residence such that they could be looked down upon as easily as they could be walked through.

The gardens of the French revolution would continue to develop and would spread to England. These two countries, while often at odds with each other, shared a common history which made the adoption of French gardening styles quite straightforward. Yet much of France maintained a Mediterranean climate, or close enough to one that their gardens most resembled the Italians. With England the differences in climate would come to define the English garden as a style and passion all its own.