There are many stock characters from “olden days” that regularly crop up in popular culture: the dirty peasant, the foppish aristocrat, the cynical priest, etc. Among the most popular of these quasi-historical archetypes is the witch. Sometimes witches appear alongside pumpkins and spider webs as seasonal décor. They are often cast as central figures, whether heroes or villains, in all kinds of media ranging from children’s books to horror films to television serials. The idea of the witch even makes its way into memes littering the internet. With so much attention on witches, and their status as figures of mystery and terror “back then,” it is worth taking a moment to understand what historical people, in this case the Elizabethans, meant when they spoke of witches.

In the Elizabethan mind, witchcraft was not simply another word for magic. Pious elites might grumble at the suspect formulae of magicians and “wizards,” but such studies were technically legal. A little closer to the mark was necromancy, the practice of conjuring and binding spirits, assumed by most authorities to be demons. Although distinct from witchcraft, necromancy was a punishable offense in Elizabethan England just the same. The key difference was that, while necromancers claimed to make devils or even the Devil their servants, witches were believed to worship and serve the Devil rather than command him.

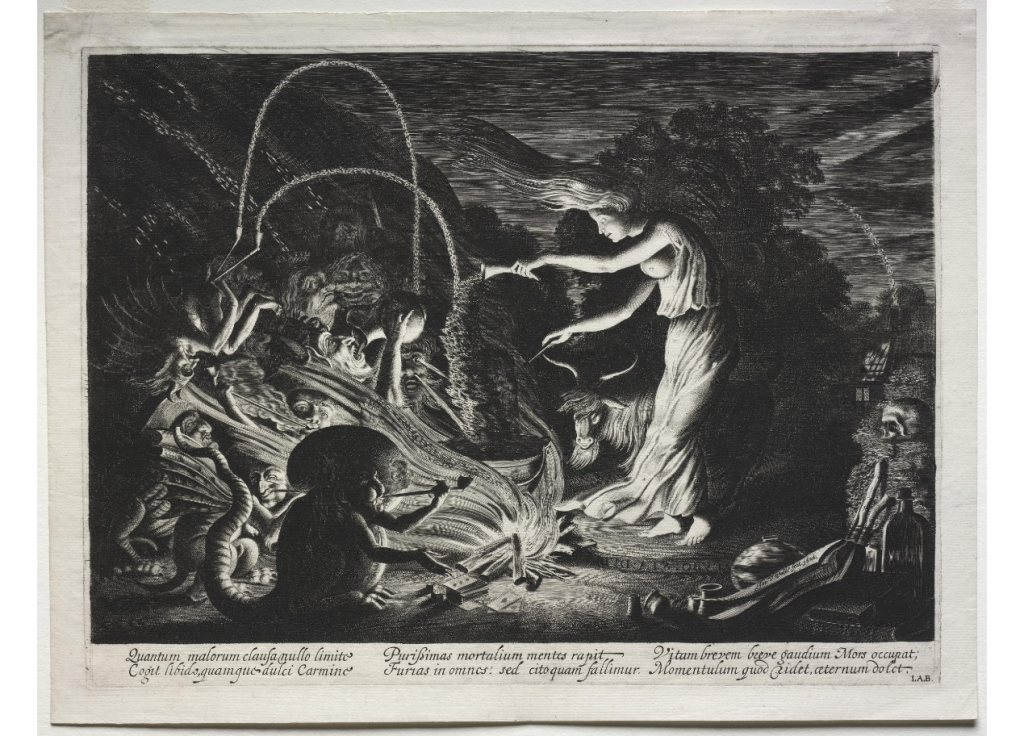

In the common understanding, a witch had not typically gone out seeking the Devil. Rather, he had appeared to them at some moment of distress or need, offering riches or revenge. Once the would-be witch had agreed to the Devil’s terms (their soul and obedience in exchange for favors and power), they were believed to seal a pact in blood with him. In some versions of the narrative, this took the form of signing one’s name in “the Devil’s book,” leaving an infernal paper trail to bind the witch to Satan. In others, the Devil bound his servants to himself by planting a “witch’s mark” on their bodies, which he could rack with pain to remind witches of their oaths and obligations to him.

The common belief was that those who had formed such a pact with the Devil went to worship him at the “witches’ sabbath,” held in a secluded place, and often in an abandoned church. The precise nature of this worship was a subject of elaborate speculation, with pamphleteers insisting to their readers that the Devil appeared as a goat and commanded witches to kiss his “hinder parts” to show their obedience. In return for their obedient worship, the Devil was said to teach the witches to make poisons and perform illusions. By some accounts, these secret meetings were also where witches could ask the Devil for favors.

These “favors,” performed by the Devil or one of his subordinates, account for much of the supposed havoc wrought by accused witches. In many cases, the exact mechanism and nature of a witch’s attack was unclear. Someone would fall ill, a horse would go lame, or cattle would die, and a member of the household would recall a vague threat or “curse” uttered by a suspected witch, frequently an elderly or destitute neighbor turned away after imposing one too many times on the generosity of the household, in the preceding days or weeks. The obvious weakness of this causal link was noted by the witch skeptic Reginald Scot, who condemned his contemporaries for blaming the random misfortunes of life on the disgruntled mutterings of poor and feeble beggars. Nevertheless, the vagueness of the threat is no doubt what made witchcraft so frightening to so many Elizabethans. A clearly defined danger can be protected against, but an amorphous one may come from anywhere and manifest as anything.

That said, a look through sources from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries does provide a non-exhaustive list of the supposed magical capabilities of witches. For one thing, the famously anti-witch James I and VI warned that witches could conjure up storms and wound, sicken, and even kill their enemies by use of wax or clay effigies (commonly called poppets). Witches were also believed to be able to spiritually “afflict” their targets, appearing in spirit or sending a demonic “familiar” to torment people with seizures and visions. More fanciful descriptions alleged that witches could fly (only by the Devil’s power, of course) and turn themselves and others into animals on a whim. Despite all these powers and the very might of Hell on their side, though, interfering with dairy production appears to have been another priority of witches in the minds of sixteenth-century English subjects.

For its part, the Elizabethan government did legitimize fears of witchcraft by criminalizing it by an act of Parliament in 1563. This “Act Against Conjurations, Enchantments, and Witchcrafts” made the use of witchcraft to murder a capital offense. Against the recommendations of anti-witch stalwarts, however, this same law mandated a relatively mild sentence of one year’s imprisonment for the use of witchcraft to nonlethally wound or sicken someone, uncover hidden riches, or make someone fall in love. Repeat offenders were assigned punishment ranging from death (in the case of wounding with magic) to forfeiture of goods (for magical treasure hunting and seduction). Thirteen years later, an act “Against Seditious Words and Rumors Uttered Against the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty” assigned the death penalty to anyone using magical means, including witchcraft, to determine when Elizabeth would die or who would succeed her, or to try to assassinate her with magic. The Elizabethan state was more concerned with material harm done by witches than any supposed infernal pacts, but these acts nevertheless shed some light on the reputed capabilities of witches in sixteenth-century England.

This has been a very brief overview of what a “witch” was to Elizabethans. As with so many Elizabethan beliefs, though, there was no true consensus. Zealous polemicists like George Gifford insisted that witchcraft was nothing more than smoke and mirrors from the Devil to test the faithful, while skeptics like Reginald Scot and Johann Weyer argued against its very existence. Nevertheless, we hope that this article has helped you better understand what Elizabethans meant when they referred to witches and witchcraft. Have a happy Halloween!

Author bio: Michael Lowry Lamble earned an MA in Museology from the University of Washington and an MA in Medieval and Renaissance History from Loyola University Chicago. His academic interests include religion, conflict, and magic. Although he could always use some riches, he knows to leave well enough alone if a mysterious figure, voice, or animal offers him any in exchange for his soul.