Levied Troops and Levied Taxes: Military Bureaucracy and Logistics in Elizabethan England

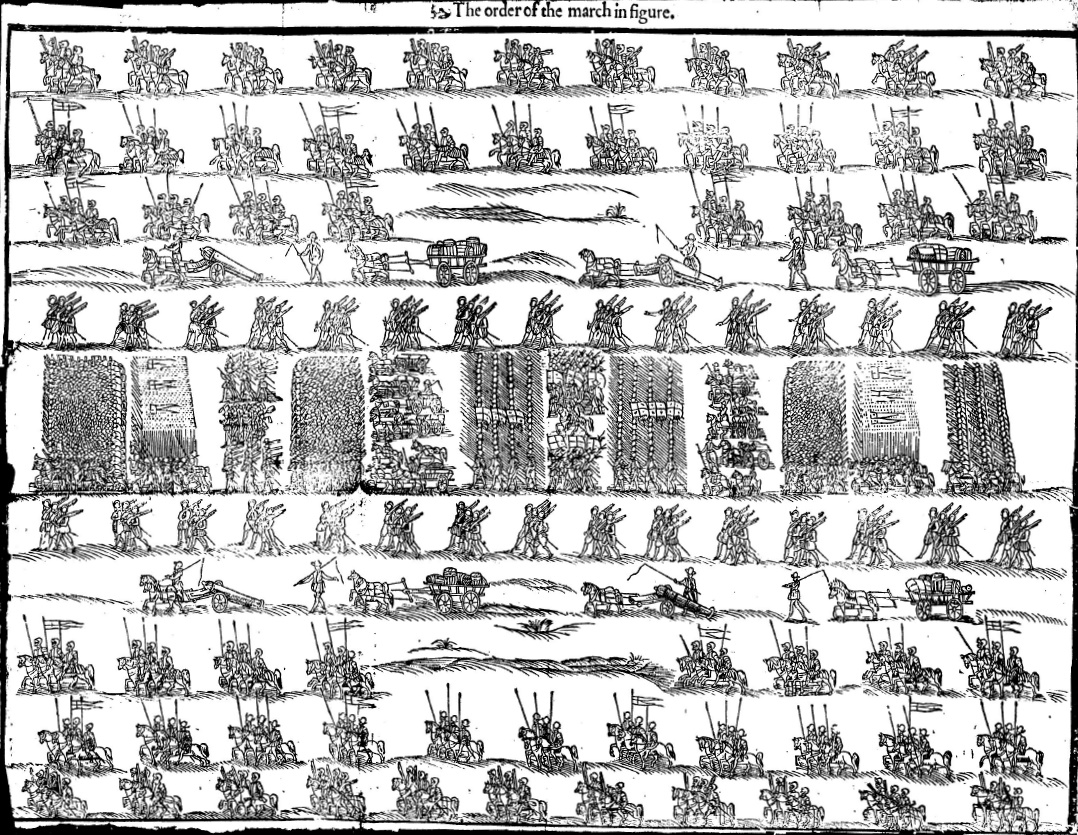

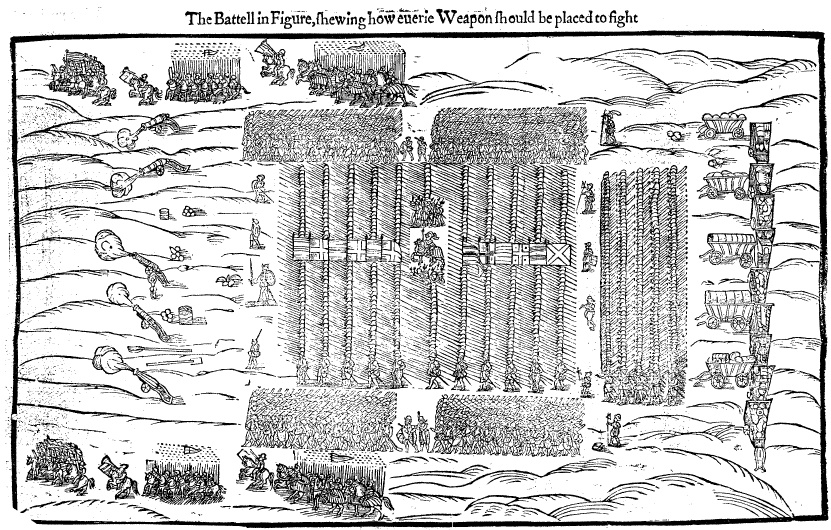

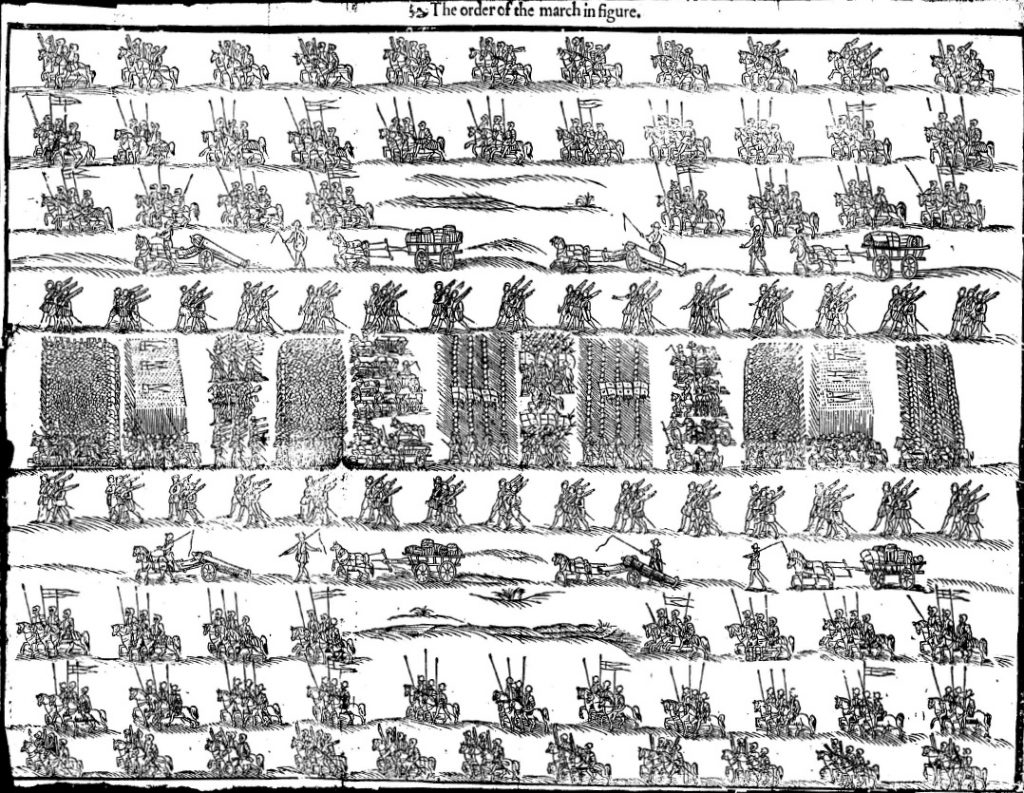

The sixteenth century was, famously, a period of great martial change for Europe. Pikemen ended the unquestioned dominance of heavy cavalry, firearms replaced bows, and siege artillery forced an evolution in military architecture. In England, however, the reign of Queen Elizabeth I underwent not just a shift in how battles were fought but also in how armies were raised, equipped, and paid for. Moving away from the Continental model of nobles raising and furnishing troops with their own funds, and often to their own ends, Elizabeth’s reign saw the development of a centrally controlled bureaucracy that gave her and her Privy Council, rather than any aristocratic would-be rival, control over the nation’s military.

Finding soldiers to fill England’s armies was a daunting task by the time Elizabeth took the throne in 1558. Henry VIII’s campaigns earlier in the century had drained much of England’s pool of military manpower, leaving Edward, Mary, and then Elizabeth a populace with little appetite for military adventures. For want of volunteers, Parliament had passed an act in the last year of Mary’s reign mandating that her subjects be prepared to serve in a national troop levy. This edict was not widely enforced, though, and what militias or town watches did exist tended to resemble civic or fraternal organizations more than fighting forces. Following the Northern Rebellion of 1569 and the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572, however, the Elizabethan government mandated the creation of Trained Bands across the nation. In contrast to the less organized militias of earlier years, the Elizabethan Trained Bands were equipped with the latest arms and armor, commanded by gentleman officers with military educations, and trained in modern tactics by professional soldiers.

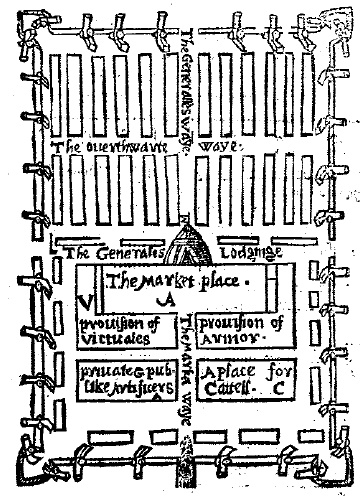

These Trained Bands, in turn, fell under the purview of the Lords Lieutenant. Appointed by the Queen and answerable to her Privy Council, these men oversaw all military endeavors for their assigned counties. They were appointed temporarily as needed in the first half of Elizabeth’s reign, but as tensions with Spain escalated, the office of Lord Lieutenant became a permanent fixture in every county by 1585. In addition to overseeing the Trained Bands and other defensive efforts, Lords Lieutenant and their staff were also responsible for raising troops from the counties for service overseas at royal command. Being important local figures, the Lords Lieutenant were better able to understand a county’s resources and military capacity than an official sent directly from London. At the same time, their position as the Queen’s agents minimized their ability to raise a rebellion against the crown, as was happening in France at the time.

Enlisting able-bodied men for home and foreign service was one thing, but arming them for battle was quite another. In 1558, Parliament passed an act mandating that English subjects acquire and maintain arms and armor according to their wealth, with a total of seventeen income brackets. On the lowest end, any person whose goods and chattels were valued at between ten and twenty pounds was expected to have a longbow, a sheaf of arrows, a steel cap, and a black bill or halberd on hand in the event of war. At the other end of the spectrum, anyone whose estates and lands provided them with an annual income of a thousand pounds or more was ordered to provide the horses and equipment for six heavy cavalrymen, horses and equipment for ten light horsemen, forty corselets (armor for the torso and thighs), forty almain rivets or coats of plate, forty pikes, thirty longbows, thirty sheafs of arrows, thirty steel caps, twenty black bills or halberds, twenty arquebuses (early firearms), and twenty morions or sallets (helmets). In the same act, the members of any given community, be it a city, town, borough, or parish, who fell below the income threshold to purchase equipment individually were instructed to collectively purchase and maintain arms and armor as agreed upon with royal commissioners. Subsequent proclamations throughout Elizabeth’s reign reiterated these requirements, taking pains to ensure that the country could shift to an effective war footing if needed. As opposed to the traditional method of leaving equipment up to the discretion of commanders, this innovation gave London greater control over how English forces would be arrayed in the event of war and relieved the Crown of some of the costs of arming forces raised under the royal banner.

Although the arms and armor purchased and maintained by the Queen’s subjects were occasionally handed over to armies organized for foreign service, their primary purpose was to equip defensive forces in England. In order to furnish those armies going overseas, Elizabeth and her Privy Council turned to other means. One method was to contract with crown-approved wholesalers who could provide large quantities of equipment on short notice. As the country moved into a period of open warfare, such monopolies became increasingly lucrative and were much sought after. The production of modern artillery, armor, and small arms was regulated, and sometimes even carried out, by the Office of Ordnance, giving the Queen and Privy Council further authority to bring the nation’s military equipment up to their standards.

For national defense, much of the costs for war fell to the counties. Trained Bands and militias more broadly were composed of part-time soldiers who could work in their usual professions in peacetime, and the mandate that subjects own and maintain arms and armor meant that such troops could be outfitted locally when the need arose. In the event that militias were mustered, as in preparation for the Spanish Armada, Lords Lieutenant were responsible for finding money to pay wages and other costs, often resorting to levying emergency war taxes.

When it came to deployment on the Continent, however, the crown had to find other means of paying for the war effort. In addition to normal state revenues, Parliament could impose a “subsidy,” a one-time tax on each individual taxpayer’s goods or lands with a variable rate determined for each payer. Elizabeth and her council were reluctant to request such a tax at first, with Parliament levying the subsidy in less than half the years from 1558 through 1584. With the move to a war footing beginning in 1585, however, the subsidy became a functionally annual occurrence for the rest of her reign. If even that was not enough, Elizabeth sold state-enforced monopolies and crown lands to make up the difference. When all else failed, Elizabeth and her government took out loans, as many of her predecessors had done. Unlike those predecessors, however, Elizabeth tended to pay her loans back.

This was not, of course, a complete, overnight transition. Some English nobles, like Robert Devereux and John Norris, raised and commanded troops by their own means. Furthermore, cities often had their own peculiar methods of raising soldiers for domestic and foreign service, such as delegating the task to trade guilds or recruiting by neighborhood. Nor was it a wholesale success. Counties sometimes failed to live up to their military obligations, and people of every station balked at what they saw as royal overreach. Nevertheless, these logistical and bureaucratic innovations, more so than any new weapon or battlefield tactic, were the hallmark of the Elizabethan military.

Michael Lowry Lamble holds an MA in Museology from the University of Washington and an MA in Medieval and Renaissance History from Loyola University Chicago. His academic interests include religion, conflict, and magic. He is not sure which 1558 tax bracket he falls under, but he has a suit of almain rivet and a few morions handy just in case.