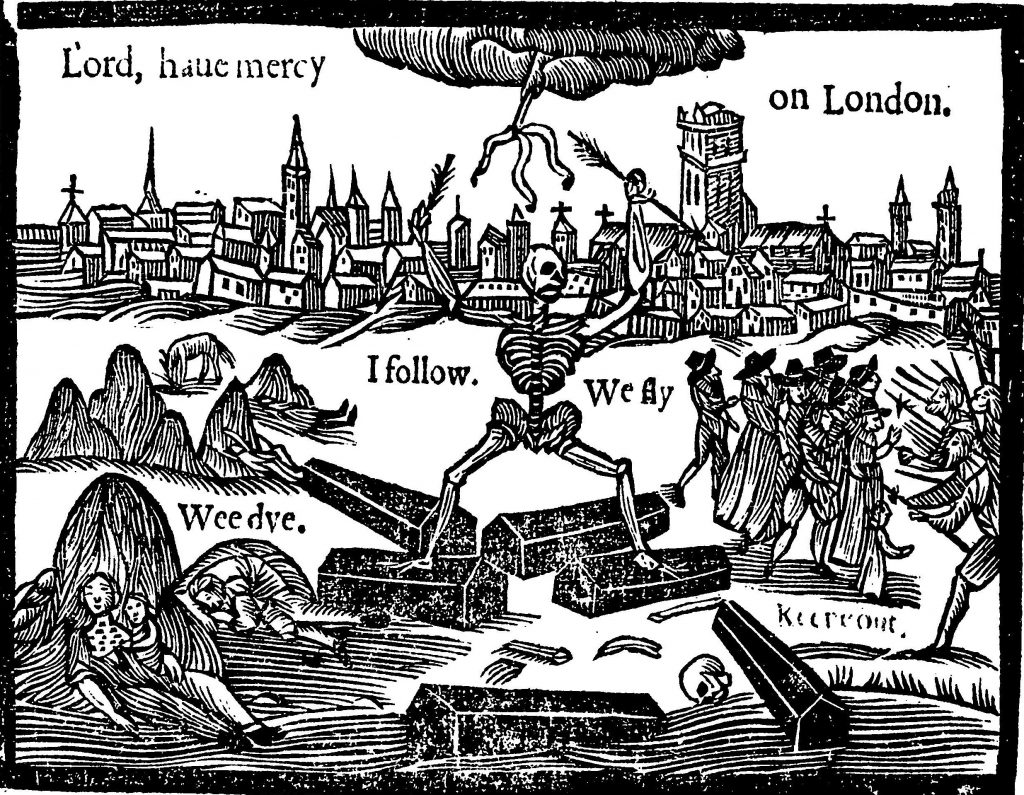

The Black Death famously devastated England, as it did much of Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa, in the mid-fourteenth century. Although this first outbreak was certainly the most dramatic, the “plague” did not simply disappear after 1349. Rather, plague reared its head frequently over the next few centuries, becoming almost an annual occurrence. For nearly the first two hundred years of the plague’s endemic stay in England, the response was handled by monasteries and religious hospitals. When Henry VIII began dissolving these religious institutions in 1536, however, sickness and infirmity were not abolished with them, and so English authorities had to find new ways to address public health.

Although monks and nuns were no longer features of the English social and medical landscape, religion remained a major component of the Elizabethan response to plague. A supplemental set of directions for worship in the Church of England was released in 1563, mandating that Wednesdays be dedicated to fasting and prayer in times of plague. The aim of this fasting and prayer was repentance for sins both personal and communal, on the grounds that if God controls all things, then plague was evidence of his displeasure with the nation.

That is not to say that the Elizabethans viewed plague as a purely spiritual matter, however, remedied only through spiritual means. In the orders to pray and fast, the Elizabethan religious authorities included stipulations that indicate an awareness that although plague was undoubtedly the wrath of God, there was nevertheless a physical component to the disease. For one thing, ministers were told to keep their sick parishioners separated from the healthy members of the congregation during services. For another, the instructions for the penitential fasting specified that only those between the ages of sixteen and sixty need fast, allowing children and the elderly to keep their strength, and exempted those already ill, a tacit recognition that skipping meals would only make the disease worse.

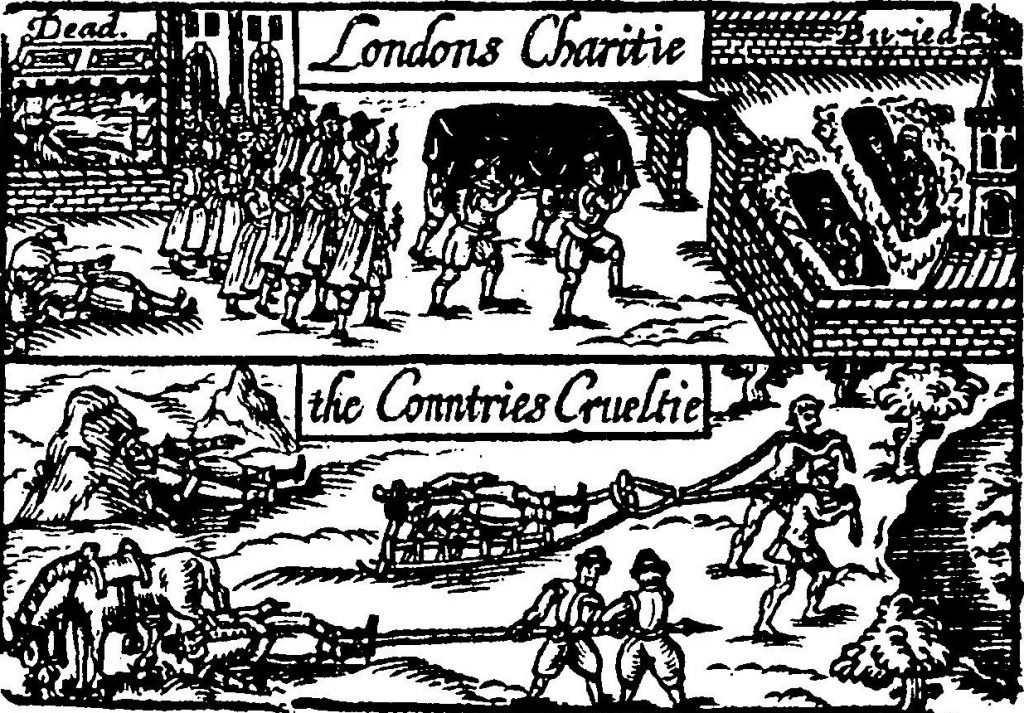

Fifteen years after the Elizabethan church instituted its emergency plan for the spiritual health of the realm, Elizabeth and her counselors released a set of seventeen edicts to address and contain the spread of contagion when it appeared. Some of these Orders are fairly obvious, if strict, steps for containing disease on a case by case basis. Households with any infected members were to be quarantined until five weeks after the last sign of infection, and inns and alehouses where infections appeared were ordered to close. The dead were to be buried in a secluded part of the graveyard at twilight, to minimize the chances of passersby contracting plague from the bodies. Once afflicted households could end their quarantine, all clothes and bedding were to be burned. To support these quarantine measures, every infected community appointed officials both to provide food and essentials to the afflicted households, and also to make sure their residents stayed put.

The plague Orders did more than mandate quarantines, however. They also laid out a groundwork for an effective and coordinated response to the plague. Upon receiving the Orders, the justices of the peace of every county were commanded to assemble to determine where infections were already occurring, what sorts of communities these places were, and their wealth. These assemblies were empowered to levy emergency taxes on the towns and villages of their respective counties in order to fund relief efforts, to appoint officials to collect and disburse these aid funds to affected communities, and to impose and enforce further preventative and relief measures as they saw fit.

Each parish was commanded to appoint “searchers” to examine the bodies of the dead and determine how many had died of plague. Every week, each parish had to report its numbers of infected and dead to the justices of its hundred (the English administrative jurisdiction between parish and county), and said justices were required to meet every week to go over these numbers and assess the situation in their territory. In turn, all the justices of the county were ordered to meet every three weeks during an outbreak to compile a report on how many had contracted or died from the plague in their county, what towns and villages were affected, how much money they had raised through taxes, and how that money was being spent. These reports were then sent directly to the Privy Council. In this way, Elizabeth’s government could monitor and address major plague outbreaks with relative detail and accuracy.

In addition to these general orders for containing the spread of plague, the Elizabethan state targeted specific threats as well. At times, the royal court was closed to all but critical personnel to protect the whole government from dying in one stroke of contagion. At others, the government forbade the import of goods from countries that were in the midst of their own outbreaks, for fear that the plague would spread to England. In times of plague, large public gatherings and outdoor markets were closed down by order or the queen.

Looking at these orders, it is tempting to think of Elizabethan England as a well-oiled machine where public health is concerned. The reality, as it usually is, was somewhat messier. There was a great deal of backlash to the measures taken to halt the spread of plague. Some dissenters viewed quarantine as antithetical to Christian charity, arguing that the solution to such a judgment from God was not to separate but rather to come together in fellowship, sick and healthy alike. Others had more worldly concerns, suspecting all the quarantine measures to be nothing more than an attempt to curtail their rights, rights which they feared would not be restored after the plague had passed. That the London authorities had a pattern of using the threat of contagion as a pretext for shutting “undesirables” out of town and conveniently forbidding public assembly at times of civil unrest no doubt fed into these concerns.

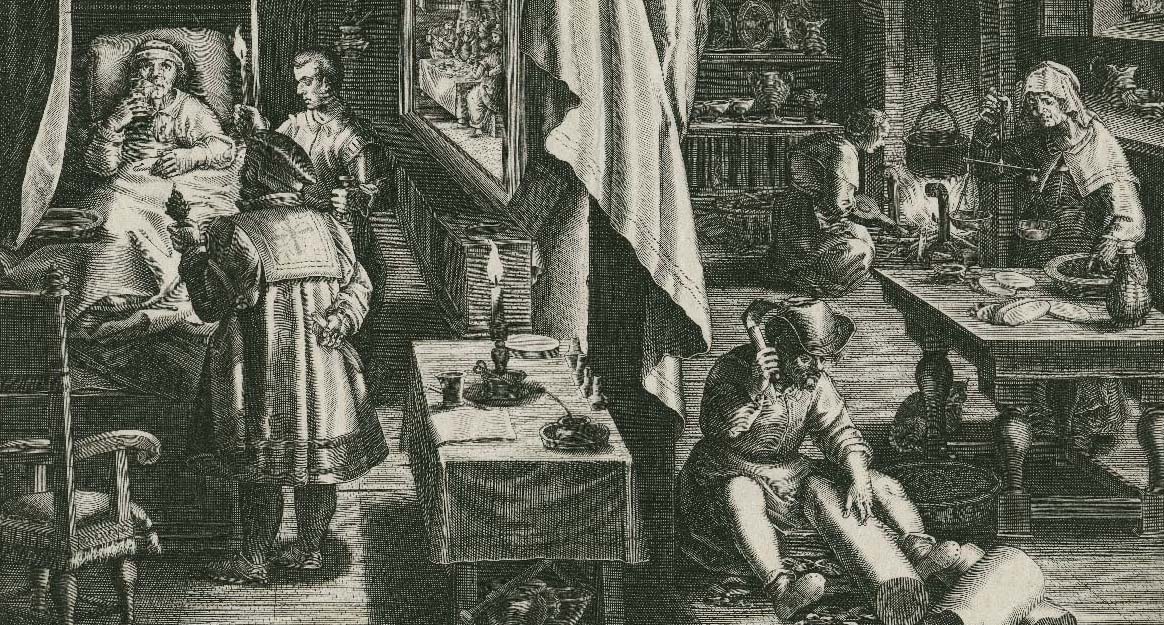

Thus far we have examined only the large-scale responses to plague, but individual Elizabethans also took steps to protect themselves. On a spiritual level, private prayer and penitence, promising to live uprightly if only God would lift his plague, was always a popular response. Looking to physical health, many recommendations from Elizabethan doctors hinged on the theory that disease spread by way of a foul smelling miasma. People were instructed to carry something with a sweet smell, such as a pomander or a handkerchief dipped in rosewater, to ward off this miasma. Going further, physicians urged Elizabethans to perfume both their clothes and their houses to discourage any infection, and to leave clothes out in the sun to air out after any contact with the infected. Prevention did not stop at perfume, however. To avoid contracting plague, physicians recommended various tinctures and cordials, either to be taken on their own or added to one’s breakfast. Bloodletting and purgatives to help balance the humors were also favored tactics for Elizabethan doctors in the fight against the plague.

For all the steps Elizabethans took to contain it, plague would remain a major fixture of English life up into the Restoration, with the last major outbreak hitting in 1665. Nevertheless, it is illuminating to see the ways that these people over three hundred years ago grappled with the fear and uncertainty of virulent disease. Some measures, like perfume and bloodletting, have ultimately proven to be useless. Others, though, like swift quarantines and thorough record-keeping, have become staples of modern public health practice. One thing is certain, however, as we examine the responses to disease of people living hundreds of years ago: It’s not the end of the world.

Author bio:

Michael Lowry Lamble holds an MA in Medieval and Renaissance History from Loyola University Chicago and is currently pursuing an MA in Museology from the University of Washington. His academic interests include religion, superstition, conflict, and identity, and he is writing his master’s thesis on the impact trying on armor has on what museum visitors learn in arms and armor galleries. At Bristol, Michael carries pike and shotte and portions out gunpowder.